Welcome to Diane’s Blog!

I’ll use this spot to chart what I enjoy and endorse, as we attempt to live a life of style in a culture of business and writing and art.

And I hope you join me; share your own stories, insights and ideas about living a creatively expressive life.

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

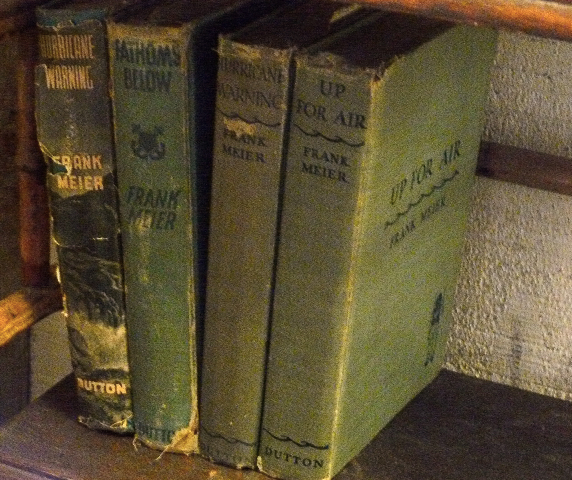

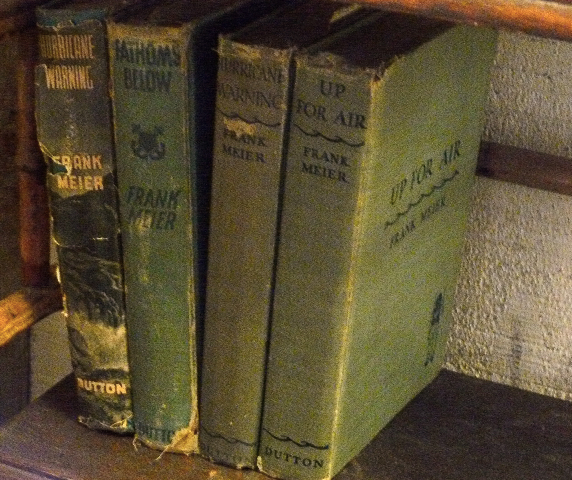

Some of the books of my grandfather, the famous deep sea diver, broadcaster and author, Frank Meier.

My grandfather, Frank Meier, wrote books with the most wonderful titles: Hurricane Warning; Up For Air; Men Under the Sea; Women of the Sea; Fathoms Below. In them, he told the stories of his adventures, and of the storms and shipwrecks that took down the vessels he spent his life salvaging, as he earned his title, Master Diver of the World. Before Cousteau, Frank Meier was the most important deep-sea diver in the world, but his real fame came from the books he wrote, their serializations in The Saturday Evening Post and his weekly radio broadcasts, where he read those same stories, each week, on the air. Above all, I think it’s clear, that along with his knowledge of the deep, this man knew how to mine his own quarry.

My mother’s mother, on the other hand, never had the chance to realize her dreams; she died at the age of thirty three, in 1933. Along with the stories of her horses stabled in Central Park and her perfectly dressed townhouse on 52nd Street, it was said that at her death, she was planning on launching her own publishing company. At least that’s the legend as remembered by my mother, eleven years old at the time of that important death. Some legends are more true than truth; especially to a child who misses her mother. But there must have been something to the story, as the idea of having one’s own imprint seems an unlikely fantasy for a little girl.

Still, even with the romance and family history surrounding writing and publishing on both sides of the parental equation, I didn’t dream of becoming a professional writer; not as a child nor as a young woman. I didn’t take creative writing classes. I never joined a writing group. And if I were more identified with Jo March than any of the other Little Women, I was also hell bent on growing up to be like Amelia Earhart. Only not dead and lost at sea, I remember specifying. And I would fly only on weekends, my time-off from my real work as a doctor. A doctor who would save the lives of the handsomest boys in school, all of whom were headed for bouts of typhoid or rock climbing injuries that only I would know how to resolve. Maybe there was drama in my blood, after all.

Of course I wrote. So did you, even if we didn’t call it ‘writing’. I’ve always loved writing letters, I took to e-mail like a duck to water. And if, in my work, the constant, massive output of words that make up a life of marketing and business consultancy didn’t seem to add up to anything exquisite or rare, I enjoyed thinking through a client’s problems and outlining their solutions, equally enjoying the crafting of the papers that informed those positions.

I still enjoy writing copy and I’ve no intention of giving up my ‘day job’. I’ve loved the discipline of getting something large enough to cause an anticipated reaction in a real live person, down to the words that could fit into the tiny space available in an ad. I’ve loved thinking through the voices that might be most effective. Do they educate, scold, plead or inform? Do you hear the voice of your favorite teacher, your big crush or your best friend? Do you hear the voice of your own heart? What wonderful exercises. Are they somehow less than literature? They’re certainly shorter. And they actually have to work. They have to stick and inspire. In a way, they’re held to a higher order than art. But, ironically and all too often, if they’re not art, they probably won’t work. Can business writing afford to be less than inspiring? Less clear? Less compelling? I hardly think so.

And while it wasn’t technically business writing, when Kirkus or Publishers Weekly called The New American Wedding both “literary†and “indispensable†I was delighted. Literary! Imagine that, I thought. But did I think of myself as an author? I did not.

My first book, The New American Wedding

If I was not a natural writer, I was certainly a natural reader. Following an accident, when I was seven, I had a series of operations on my hand, which kept me from playing with other children for about a year. I may not have gotten much fresh air, but I read. I read every book in my parent’s houses and nearly every book in the school library. These libraries were dangerous places, they held all kinds of adult information. My fifth grade teacher found John O’Hara an inappropriate choice for a ten-year-old’s book report. Ten North Frederick was rejected and I was instructed to write a second report on Black Beauty. I’m still annoyed.

But I read everything – books, pamphlets, magazines, the labels on products, instructions in packages, and every magazine or newspaper that came to or near our home. I found I liked what became known as the New Journalism even more than books. The magazine of the New York Herald Tribune (to become New York Magazine some years later) was a Sunday treat from the time I was about eleven years old. It presented a new version of an adult world, much more exciting than the land of town-and-country clubs and the cardigan-sweatered Junior League served up by my parents. Each week my fashionable aunt would drop off her stack of Women’s Wear Daily issues, and I would inhale them, memorizing the names of the top models and the chicest boutiques and hanging on every word of Suzy’s gossip column. I was as delighted as my mother was dismayed to find that her hairdresser, decorator and butcher were all at the top of the WWD Most-Wanted list. In restaurants and shops all over town, I would point out Euro-trash countesses and effeminate dress designers to my horrified parents, calling them by name. “Don’t point,†they would hiss, but almost always followed by the completely bewildered query, “How do you know these people?â€

I knew them, as well as I knew the characters in John O’Hara’s fictional town of Gibbsville. I knew them through the pages of print that took on much more meaning than most of the neighbors and families who peopled my real life. I wanted to escape into those far more interesting, glamorous and salacious fictional lives than those I recognized ferrying between the Upper East Side of Manhattan and Morris County. But did I dream of creating such characters myself? I can’t say that I did.

Still, when it appeared, in my fifth decade, writing fiction came about as naturally as making a pot of tea. I had an idea for the story of The Season of Second Chances; a tale about two unlikely companions, outcasts, united by their emotional limits and facing the chance to change their lives – together or apart. I had the most encouraging cheerleader in Frank, to champion that idea into a commitment, and to direct me into its exercise. Not terribly different, I found to my pleasure, than the creation of a marketing campaign. Not terribly different than the hundreds of White Papers I’ve produced in my decades of work. But it is different, of course, in that it is, of all surprises, even more fun. Solitary, indulgent and delightful, if you can create characters with whom you look forward to spending time, people with ideas you long to explore and values you want to champion. They didn’t need to be real, but they were real enough for me. And I found I liked writing fiction. A lot.

I don’t know whether that’s what spurs on other writers. I don’t know whether Mellville always wanted to write, or if, when he did, he simply wanted to get to know a whale a little better. I think my grandfather wanted to tell his own stories, revisit the places and the times that gave him such success and energy. I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to imagine that when he was land-bound, he longed for the sea, and his writing brought it back to him, like a warm wave on an ocean of memory.

Maybe we all long to visit the places that originally inspired us, or brought us comfort or delight. They might be actual places – or perhaps they’re truly deeper regions, fathoms below our consciousness, where the idea of creativity – producing something in your own unique voice – called “literature†or not— is realized and allowed to surface on the sea that becomes your life.

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

The first in a never ending series of tips from Teddy—imagined or otherwise.

In The Season of Second Chances, handyman-extraordinaire, Teddy Hennessy, may be emotionally blocked, but his power shows up in a talent to blend high and low solutions with equal grace and practicality. It’s the kind of genius that has made the magazine Real Simple essential reading for so many.

Through most of the book Teddy is renovating our narrator, Joy Harkness’ tumble down Victorian home. And while he knows, as well as any architectural historian, every move in putting the puzzle to rights, – from the perfect newel post to colors William Morris might have chosen himself, Teddy shares brilliant short cuts that might stretch Joy’s budget or keep things moving quickly so that she doesn’t find herself living in a depressing job-site too long.

Joy’s home office is a great example. Teddy creates a room of charm and efficiency on the fly. For instance, he takes two old bookcases, of no particular value, and cuts them in half to create the look of built-ins. Joy tells us about it here:

On the far side of the room he put my old bookshelves, now divided into four sections only waist high; he screwed them together, added a top and some molding and painted them the same color as the wainscoting behind them. Instant built-in bookcases!

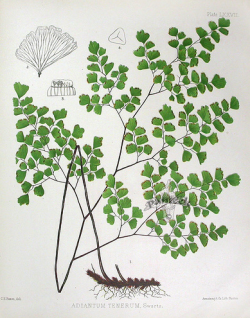

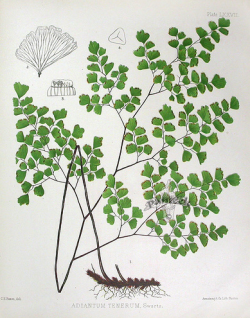

Teddy Hennessy used pages from a book of fern botanicals to detail Joy’s home office in The Season of Second Chances. Framed prints are an inexpensive way to get a cohesive design theme going in a room that needs focus and style.

We can see that Teddy’s immediately given the room a look of fitted architecture. He created a desk from two filing cabinets, a hollow core door and some legs. The town fabric shop stitched up a kind of slip cover – closed on three sides and open on the desk chair side, out of khaki colored canvas.

He ordered a glass top and underneath the top he randomly placed Xeroxes of pages from a botanical book on ferns. Frankly, I didn’t understand the ferns, but he took more of their pages and matted and framed them in a long, low line around the room and I had to admit, it was beautiful.

Teddy painted the little room sage green with creamy white trim and wainscoting. He hung a craft paper window shade on the one long window and painted the bottom with dots of sage green. He painted an old wooden desk chair found at a consignment shop, and had a remnant of dark green carpet bound to fit, nearly wall to bookcase. We can see the room and understand how quickly it must have come together. He gives us the hints to do the same:

- Creating the look of built-ins with a bit of simple carpentry, molding and paint can give a room focus, style and practical authority all at once.

- Carrying a line of wainscoting or chair-rail and the discipline of two colors will further organize a room with very little effort.

- A desk can be fashioned for next to no money that will not only be functional but as attractive as a large, impressive, expensive desk.

- The discipline of a repeated theme – in this case the fern botanicals, on desk top and walls, can create a mood and a deliberate sense of style faster and more powerfully than trying to make sense of a room full of valuable decorative items.

- The simplest solutions – a craft paper window shade – need not be thought of as a compromise. Its appropriateness makes it beautiful. The embellishment of wit or detail – in this case, the little painted daubs of green, make it personal and give it warmth.

Teddy’s hints are found all through the book. All equally sane and generous. Nothing you can’t take in and learn from – as you read about two characters facing the possibility of change in their own lives. If they are each equally frightened to face a second chance, neither shirks their professional responsibilities and both share them with us – all through the book. More of Teddy’s ideas to come. And Joy’s ideas about reading and writing – check in often.

Thursday, November 12, 2009

Sunday nights are, for the moment, sacrosanct. At ten o’clock, I turn to AMC, and the glass-walls and flat paneled doors of Sterling Cooper, with its integrated ceiling lights and mid-century mix of Asian and International School detail, bring back a moment of my past so Proustian, it might as well be madeleines and tea.

My introduction to the world of advertising and promotion was a decade later than the 1960 moment when we first meet the Sterling Cooper gang. The industry’s insight about media and marketing were much farther along than the primitive images of Mad Men sitting around a Philco television. But physically, the look of the offices was much the same, and socially, things hadn’t really changed all that much.

For the first ten years of my professional life, I would volley back and forth between Avon and Revlon, Ogilvy and NW Ayer, and a few national retailers, with brief stints at most of the major agencies and a few of the smaller, hipper shops thrown in for good measure. I was hired inside cosmetic companies (and a retailer or two) to launch products or departments, and with agencies, as a kind of free-lance-wild-catter, to land a particular (and usually cosmetic) piece of business. We rarely failed to land the account we’d aimed for, but after six or seven months observing the culture of the agency, I never wanted to sign on as staff and work on what we’d won.

Only Ogilvy seemed a place of any real civility, with a demand for serious, professional behavior. David Ogilvy was still very much alive and vitally, if infrequently, attentive. Jock Elliot and others walked in his footsteps and maintained the good practices. Ogilvy, alone, was a place I could admire and would hope to emulate, but none of the agencies, not even Ogilvy, provided a place of comfort or apparent opportunity for a young, ambitious Art Director/Creative Director who happened to be female. At least not in my own moment.

I got an overview of agency culture in the early 1970’s, few outsiders would have seen, and fewer insiders would have had the distance to recognize. I was a girl in a man’s land. And I’d been positioned right at the sweet spot at two of the largest cosmetic houses in the world. I knew their issues, their executives and their aesthetics. If the agency wanted some insight into the companies they were pitching, and some enlightenment about young women and cosmetics, I was their girl. But the men who brought me on board were rarely the men I would work with on a daily basis. They were the Big Boys upstairs, parent-age to me and even to the hip Creatives who were all about ten years my senior. I was imposed on the Creative Boys. It was clear. Some of them couldn’t believe their agency had hired a girl as an art director and rarely missed the opportunity to tell me so. More than one of the bullpen artists (the men whose job it was to sketch out our ideas) refused to take direction from me, and since I wanted my work to look more fashion-beauty editorial and couldn’t get the look out of their cartoon-style anyway, I had to develop my own way of creating layouts. I just did them myself. The Creative boys had one more thing to sniff about, but we nearly always landed the business.

In the years I trudged about NY agencies, I can think of running across only a very few women art directors: the most interesting to me was a mysterious Rosalind Russell type, referred to as Miss Tobey, who specialized in ads for children and babies. She must have been in her forties at the time, and she wore a hat and gloves to work each day. Her clothes were clearly expensive, but had been chic a decade earlier than our own hip British Invasion moment. She was referred to as a legend, but she was, depending on the day or the man, either invisible or barely tolerated by the fellows who made up the Art Department.

Regardless of Salvator Romano and his lack of status at Sterling Cooper, by the Seventies, the glamour of the industry was in the Art Department. The AD’s and young Creative Directors might not have all looked like Michael Cain or Jean Paul Belmondo, but you could see where they were taking their cues. They wore their hair long before anyone in business could. Their clothes were British, and ran the gamut from Saville Row suits to band uniform jackets over tight, long, boot-cut jeans. There were more than a few Edwardian ruffled front shirts, ruffles again at the cuff – tucked into jeans so tight and unwashed they could have walked to the men’s room themselves. Their spectacles were aviator large, or John Lennon circles and often dark-worn indoors. How did they judge the Pantone chips you might well ask. I know I asked.

I knew one Art Director who had brought his pet hawk to work, perched him near his desk and fed him mice. There was blood on the carpet of his office. I heard that the building management made him stop. Creatives smoked pot openly in the office and kept bottles of cognac and scotch on their desk tops. The homeliest of them, tubby or short or frog-faced, still had an aura of entitlement as they openly assessed the figures of passing secretaries, like work crews looking at strolling streetwalkers. These were not the kind of professional offices our parents might have imagined.

Creative women appeared occasionally, from other floors, usually below us, where they incubated in copy pools, and nearly always worked on the “womens†accounts – cosmetics, fashion, babies. There were some legitimate stars who managed to escape and become important beyond the retail or agency departments. Jane Trahey (What Becomes a Legend Most and It’s Not Fake Anything – It’s Real Dynel) did only fashion. Shirley Polykoff (Does She or Doesn’t She?) wrote for Clairol. Neither of them broke the barrier of girly products.

Everything else – food, household cleansers, furniture and certainly cars, liquor, cigarettes – these were managed by male copywriters. It’s why Mary Wells seemed such a heroine. She might have been a copywriter, but at least she worked on real products – not just women’s things. She made real money. Her name was on the door of an agency that managed airlines, for heaven’s sake. But I’m not sure how many women she promoted. It was a sad field in which to look for mentors.

A card for the launch of MEIER in 1979

We all had secretaries. They sat outside of our offices, just as they do at Sterling Cooper. Until I opened my own agency in 1979, my secretaries were assigned by the firm’s personnel departments; always older than I, usually by twenty years or more. In the chic hot agencies, secretaries were rather like stewardesses. A bit of age or weight might get you assigned off of the Creative floor and on to some Siberia, like Media Buying or Billing. Or – god forbid, as secretary to the new Girl Art Director. Me.

I’m sure it’s colored by my youth, but my lingering impression of the social scene was that most of the pretty young secretaries were having sex (or at least engaging in make-out sessions at PJ Clark’s) with the hip Art Directors. And even the sex was ranked on a professional ladder. The AD’s had the secretaries, Creative Directors had their pick of the most desireable secretaries and receptionists – who were the real lookers (since they didn’t need to know how to do anything but sit there and look pretty), along with the most attractive young women from the step-up-in-status-better-paid copy pool. And at every agency I worked, there was always at least one beautiful and bright Copy Chief having an affair with a married boss; one of the guys upstairs. It was as though Central Casting had gone ahead of me and filled the positions.

Recently, Mary Wells Lawrence and Charlotte Beers (former chairman of JWT and Ogilvy) presented a collective note on-line that suggests Mad Men has got it wrong. They claim to have seen far more chic and powerful women in advertising in the early Sixties, than Sterling Cooper’s mousy copywriter, Peggy Olsen, might suggest. Phyllis Robinson, the DDB Copy chief who hired Mary Wells, was certainly one. But Robinson’s name was not up on the door with Doyle or Dane or Bernbach -- or anyone else.

So I’m not sure where they were standing, Charlotte and Mary back in the 1960’s, with this grand view of important and powerful women, leading the field. But I can suggest that you take a look at the

Advertising Hall of Fame. Out of the 183 names listed, twelve are women. And that’s not a list from 1960. It’s posted on their website today.

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

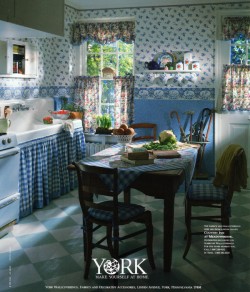

Penwork mirror by June Meier and Kakia Livanos and paisley wall by Diane Meier in the foyer of MEIER, 907 Broadway.

In

The Season of Second Chances, my protagonist describes a colleague’s office as so personal, so full of intimate and residential objects as to be ‘completely inappropriate’. Through the book, I looked for ways to create contrast between these two professional women. Josie O’Sullivan, a world-renowned scholar and Amherst professor of French Literature, brings Cordon Bleu-quality lunches to her suitemates each day. Joy Harkness, our narrator, can barely manage creating a tuna sandwich, has never had a guest to dinner nor made an attempt at decorating a home, no less her office. And yet she is very clear about her belief that Josie’s office is far too domestic to house the creation of any serious work. I mean for you to wrinkle your nose.

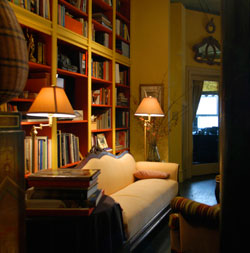

A place to sit and read in our Edwardian Library

I hope you begin to realize that Joy is an unreliable narrator, in this as in so many other things. But I also want you to go back and try to think when, if ever, you were in an office that carried the mark of its owner to any great extent. I’m banking on the fact that you can’t easily bring one to mind. Neither can I. And I’m in the biz, so to speak.

So what’s that about? These rules that keep our talents and our personal expression separate, depending on the venue or the activity?

At

MEIER we imagined a very real customer for our client and then we imagined her kitchen with the fresh patterns of wallpaper and fabrics from York. Our work in designing the logo, as well as the ads.

Because it’s not just the line people draw between home and office, it’s the idea that with the exception of Interior Design (which carries with it the equally devastating punch that a decorator

must live in a showcase), what one does for work (window dressing, set design, art direction, prop-styling)

wouldn’t have its natural exponent in one’s real life. As though they’re surprised you didn’t “keep it all†for art or commerce.

Frankly, I don’t want to believe that there is a completely separate intellect or instinct for creating the environments of the

imaginary lives in ads, as distinct from creating environments for real live,

breathing people. And I

won’t believe that there is a reason the ‘office’ where one works, needs to be any less personal or authentically articulate about one’s life than a home. Why – when we spend the better part of our week within these walls—why would we not create an environment that expressed our lives, our loves and our values? Why not indeed?