Welcome to Diane’s Blog!

I’ll use this spot to chart what I enjoy and endorse, as we attempt to live a life of style in a culture of business and writing and art.

And I hope you join me; share your own stories, insights and ideas about living a creatively expressive life.

Tuesday, October 05, 2010

There have been a lot of questions this past year about the difference between my day job in marketing, and the writing of my first novel.

“Not so different,†I’ve answered to the surprise, apparently, of many.

Serious marketing requires serious communication. And great advertising copy comes from a deep understanding of your markets, your target customers, the lives they lead, and the way they express themselves. So, putting my characters into a story, wrapped up in a book cover, was not dissimilar to imagining the lives I believed might be graced by my clients’ products.

There is one major difference, however, and there is no getting around it. In marketing, I am not paid to produce things my clients like. I am paid to produce results. Whether the corporate president or his wife likes the color blue in the their logo, or appreciates the headline of their ad, is only of passing interest to me; I can’t let myself be distracted. I am not talking to them, I’m talking to their customers. Criticism of my work in marketing is not subjective. The campaign worked, or it didn’t. While its always a pleasure to be recognized for one’s creative work, my fulfillment comes from the undeniable ways in which that work functioned.

But sending a novel out into the world, that’s a whole different kettle of fish.

The July before we launched, the folks at my publisher, Henry Holt, told me that they would be submitting The Season of Second Chances for Amazon Vine reviews. They didn’t say this with bright smiling faces, I noted. They said it with furrowed brows. Publishers aren’t in control of those early reviews, they explained, and many feel that the Vine reviewers take their role of gatekeepers so seriously, that they may keep some good content from reaching a target audience.

“Okay,†I said, “So, don’t do it!†I mean, I’m so nervous about the idea of reviews at all; if you have real worries, why tempt fate? But I was not in control. I stewed from July until February, if “stewing†can possibly be an accurate description of my state of mind. In fact, as the publication date neared, I was almost apoplectic about the whole idea of being reviewed by anyone and everyone with a pen or a keyboard. I became unreasonably nostalgic for the old days when a handful of professional reviewers, in a gaggle of newsrooms, could sink you in a week. Today, you can be pecked to death over months or years — by hundreds of disgruntled readers, citizen-reviewers with axes to grind, little training, a sense of personal power, and no editorial body to whom they answer.

My fears were, for the most part, unfounded. My reviews have been overwhelmingly lovely; thoughtful, careful, respectful, and positive.

Big exhale.

The harbinger of the biggest repetitive thorn showed up that first week in the aforementioned Amazon Vine Reviews. In a sea of five-star raves, there was one two-star note with the headline: “My Chick-Lit-Loving Wife Hated This Book. Too wordy,†he said. “Too many references she didn’t get. Too much not like Chick-Lit. Very bad. Very disappointing.â€

Except, of course, I wrote a book that makes reference to Sontag and Beckett, Shakespeare, and Mary McCarthy, Alma Mahler Gropius Werfel, for god’s sake, and W.B. Yeats. I even talk about the books my protagonist holds dear her–Edward Sapir, Bullfinch and Brewer, Van Doren, and Campbell. And all through The Season of Second Chances, there are references, inside jokes, and bits of play with our heroine’s major subject of study: the Gilded Age Literature of Henry James and Edith Wharton. Even her dog is named Henry James. I’m not surprised the Chick-Lit Loving Wife didn’t like the book. But while he may have been blaming the hot dog for not being ice cream, the review sits there on the Internet, and probably will do so long after I’m gone.

And, from there the thorn catches–as it turned out, nearly every serious review The Season of Second Chances landed found some way to mention Chick Lit. It is far smarter than Chick Lit, they claimed. Hurray! It isn’t Chick Lit at all! Hurrah! And for those who felt that it was just a shame that anyone would mistake it for Chick Lit, a bone was thrown with the label, “Women’s Literature.†As though we’d all think that was so much better. What happened to calling it…Literature? Or just good old-fashioned, Fiction?

There were a very few reviews that just got the whole thing wrong. And if you’re anything like me, you might want to write to each of them. Or track them down and stand outside their house, and wait until they come out, so that you can angrily correct them. One person suggested that I’d not done my homework and then listed the things about which she knew better. Except that I had done my homework, and she was just plain wrong. Another found one character in the book, quite unbelievable. And it was the only character I’d taken from life.

You will want to run through the town with the magazine or web page in your hand, showing it to everyone who will listen, grabbing them by the lapels, shaking them, and telling them how very wrong-headed this review is. Your husband and your publicist will keep you from doing that, because they know better. And you will think that they are part of a vast conspiracy to keep the truth from getting out.

In my day job, I was comfortable in the cold arms of irrefutable truth. I could banish the subjective criticism and keep it from hurting me. As a novelist, the subjective of how someone connects to your work is the object of the exercise. I’d like to tell you that it’s going to be better for you. But it won’t be. Somewhere, even in the wonderful review–the one that sounds as though your mother paid someone to write it–there will be a line or a reference to something they liked, and your head will pop up like an infield fly. “That’s not what I meant,†you’ll say. Or, “Mary isn’t the one who wore the hat!†Or they’ll quibble with some small thing, in contrast to all the other marvelous things they claim you did in your masterpiece. And you will only remember that quibble. “Who are they†you’ll ask yourself, “to pass such judgment?â€

They are your readers. But they aren’t all of your readers. Try, try, try to remember that. And if you’re ever going to write again, I’m told, you have to learn to let it go. Let me know how you do.

Thursday, September 09, 2010

It went up last Thursday evening, but by early Friday morning there were already a dozen comments about the Slate article that proved the predominance of book reviews in favor of male authors in The New York Times. There it is, in empirical black and white:

"Of the 545 books reviewed between June 29, 2008 and Aug. 27, 2010:

—338 were written by men (62 percent of the total)

—207 were written by women (38 percent of the total)

Â

Of the 101 books that received two reviews (both the Book Review and a ROP review)Â in that period:

—72 were written by men (71 percent)

—29 were written by women (29 percent)

Â

What does this tell us? These overall numbers pretty well line up with what other studies have found: Men are reviewed in the Times far more often than women. As for the double reviews, men seem to get them twice as often as women. "     Â

Â

Â

The argument, at least in the Big Print of Huffington Post, a host of Internet stories, and the little print of Twitter, was ramped up a few weeks ago, amid the Jonathan Franzen hoopla, when

Jodi Picoult and Jennifer Weiner brazenly suggested that his attention was evidence of yet another "white man" stealing all the oxygen in the cultural conversation about contemporary fiction. They made many valid points, and a number of those points certainly can be seen to illuminate prejudice, or at least suggest the way the culture (and I'd suggest it's not just

The New York Times, but all of us) view and value the work of women.

Â

As you might expect, given my own public history with the Chick Lit/ Women's Lit argument, I was tempted to enter the fray. But Picoult and Weiner were carrying spears that I thought likely to confuse the message, if we're going to pierce an environment of inequity.

Â

The staking of claims based on their success with popular, genre fiction, vs. Franzen's literary reputation, made Picoult and Weiner seem like bad sports. And I don't think that's what they meant. This is not

their argument –

it's all of ours. If we're not clear and careful, if we align ourselves with positions, however well-meaning or rooted in legitimate frustration, that allow reasonable people to question our logic, we're sure to lose the larger battle.

Â

The problems and issues of prejudice are, of course, massive, pervasive, insidious and nearly impossible to untangle. It is very easy to jump to larger conclusions before smaller issues have been illuminated or resolved. And it is just as dangerous to miss the big picture as we stand at the side, trying to untie a small but difficult knot.

Â

Weiner and Picoult write books that fit nicely into the category of Chick-Lit – or "Popular Genre Fiction", a valid category, parallel to Mystery, Sci-Fi, Thrillers, Romance, etc. That they may be well-written and are certainly well-loved is not the point -- exactly. At least, it's not the Jonathan Franzen point. Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett transcended Mysteries to a status of cult-following in the literati-culture. The seriousness with which Stieg Larsson's books have been taken, the attention Nick Hornby gets at every level of print and Internet – these examples are the real meat of Jodi Picault's and Jennifer Weiner's argument. And they should be.Â

Â

Genre literature makes sense. It appeals, if not like a fetish, then certainly like a clarification of choice. A literary nod to popular restaurants –

I like Chinese. You like Italian. Â It took decades of attendance for Mexican, Turkish or Korean eateries to be listed in New York tourist guide books. Marvelous, ethnic-cuisines, to be sure, but until

The Underground Gourmet, it didn't register with publishers that anyone outside of the specific ethnic communities might be interested. If a city in America were largely made up of an ethnic group and its traditional restaurants were never reviewed or noted or listed, there would (and should) be an eyebrow raised. That's what Picoult and Wiener are saying.

Â

But here's what I'm saying: if Eric Ripert's Le Bernardin were to be referred to as a Chinese restaurant because he'd made use of bok choy and ginger in a few of his recipes, there would be hell to pay in Foodland. And Anthony Bourdain wouldn't be the only one ranting.

Â

The Chick Lit argument as positioned in the Franzen Debate clouds the issues to mix all kinds of cranky, if valid, complaints:Â

Â

• Why doesn't The New York Times review the books the American Public seems to want to read? And if most of those books are by and for women, this is a valid argument, to be sure. Though I would still suggest that there is a need for an overview of the kind of material that will move the culture forward, not simply fill it's belly. And the likelihood that many of those books would be authored by women seems just as obvious. (We might better ask – Why is The New York Times Book Review so god-darned boring? But that may be another story, altogether.)

Â

• Of the few "popular" or "genre" books reviewed or profiled in what's left of the directional press, why are women authors represented with such a disproportionate share? Another valid question – since they make up the reading, buying and authorship population to overwhelming numbers.

Â

• And my favorite question: Why must we paint fiction that happens to be written by women, about contemporary female protagonists, facing everyday issues of family, career and home, without the benefit of guns, heroin or extra-terrestrial devices, with the Chick Lit brush – or – as a bone thrown to suggest respect --- as Women's Literature or Women's Fiction.Â

Â

Let's keep apples with apples and genres to genres. If Franzen is seen as worthy of respect, and his work is not referred to as Men's Fiction, then why are Alice Sebold, Anne Patchett, Anna Quindlen referred to consistently by their gender?

Â

Today's New Republic piece takes the issues one step further.

http://www.tnr.com/article/books-and-arts/77506/the-read-franzen-fallout-ruth-franklin-sexism .Â

Â

Why indeed, has the New York Times NOT responded to Slate's damning proof of prejudice?  And even in the subsequent articles around the news of this study, I'm not seeing much public outcry beyond cranky observance.

Â

I think it all comes down to the fact that men are not "doing this" to women writers. We all seem to think that the domestic lives of women have little value. Women will, of course, read Franzen, Roth, Larssen, Delaney, Michener, Updike, Vonnegut, Doctorow, McCann. But where are the men reading Quindlen, Patchett, Kingsolver, Berg, Tyler, Morrison, Straut?

Â

What are we doing in the ways we raise young men to read and value a woman's perspective? Until we can grapple with these issues, it's unlikely the value of our output will transcend the worth we assign to our lives.

Tuesday, August 03, 2010

Yesterday, a favorite blogger, www.amidlifeofprivilege.blogspot.com, wrote a piece about the imagined gardens of the Betty Draper (via Mad Men) household.

Because of my own professional tangent to that Mad Men world, I found that I hadn't connected much with the personal home-life of the characters. I just wanted them all to go back in the office, where, it seemed, my own real-life had begun. But this blog reminded me that the ideas we took into our lives of promotion and marketing were learned at the most basic levels in the Mid-Century households like those that surround the Mad Men characters.

My parents were different than the Mad Men families we see splashed across the screen. More discrete and more guarded, they managed a kind of polished, conservative, beyond-reproach façade that held their natural creative talents in check, and took years of therapy (and affection) for me to de-code.

Their gardens were only a small fraction of the lessons learned, when I didn't know I was learning lessons at all. And while "Amid Life of Privilege" asks us to remember the Mid-Century gardens of our parents, I will remember one more; our city garden – the domain of my great-grandmother, who against all odds, grew spectacular roses from May to October. The legend surrounding the garden has someone, like James Amster, a friend of Mother's, and the creator of Amster Yard, asking my great grandmother how she managed to grow these roses – healthy, beautiful, rich with color, some as big as baby's heads. "I only grow what loves being here," she explained, with a kind of clean, practical, if sometimes heartless, Yankee efficiency. And that lesson, as much as anything, has become a large part of my own morality.

With that said, here is my memory of my parent's country garden, as prompted by "Privilege":

We spent weekends and summers in Morris County New Jersey -- and very much in the time of the Drapers. When I think of my parent's country property - perched high above a lake and surrounded, for the most part, with woods, the acreage that they chose to control was just that-- controlled. Azaleas ran down the path to the front door, the back terraces were floored in herringbone brick and the pool was dressed in lines of fire bush. A step up to a grove of trees on higher ground was bordered by a defined run of planters that held the expected tulips in Spring, impatiens in Summer and mums in Autumn. If the wild blackberries that grew along the deep length of the post and rail fence, had been a gift of nature, they were certainly not allowed to swallow the fence with their own intended abandon. They were 'controlled' like every other living thing on the property. Very Mid-Century, if you think about it.

Since my parents were both pretty creative interesting characters, I suspect that what I am remembering, is just what "Privilege" is talking about -- a Mid-Century idea of what a garden was "supposed" to look like. A blend of acceptable references that made the gap between the 'haves' and the 'have-nots' blur into a tasteful and controlled ideal.

If others had to push toward some level of public authority, we had to keep a lid on our self-expression, never allowing a hair of ostentatious or "showy" display to mar the perfectly groomed control of our well-bred facade.

This morning as I left our CT property to head back to NYC, I saw the first huge (big as a paper plate) hibiscus bloom of the season, bright and unabashed, in an impossible, almost phony, clown-nose red. It's planted in our Red Garden - a riot of all things red -- roses, lilies, dianthus, hibiscus, fuchscia, clematis, impatiens and more each year - all backed by barberry - with its own red-burgundy foliage.

I know my parents might have come to this eventually, had they lived long enough to enjoy the fun of gardening; just to see what you can actually do when you put a little personal creativity to the task. But back in the 1960's, it must have seemed too dangerous to even think about. Whatever may have made it "not worth the risk", I just can't imagine, but isn't it nice we have the chance now - on our own - to do what we will!

Thursday, July 15, 2010

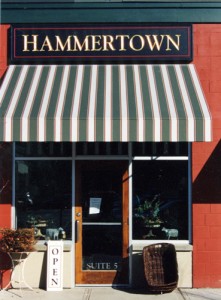

While I know I've mentioned them often and fondly, I don't believe I've ever written a blog about Hammertown Barn. And now I find them popping up this morning on Yahoo as a vendor to Chelsea Clinton in the Clinton Wedding story! It's a little like finding out that Miss Boulanger, the fabulous woman who gives you piano lessons, is world-famous Nadia Boulanger - a verification of all you thought on your own, but still a wonderful surprise.

The Hammertown Barn location from whence Chelsea's pillows were proffered, is Rhinebeck, New York, the legendary Hudson River town of the wedding. My Hammertown

Season of Second Chances book signing was in that very spot. And it is a town, in the words of the Michelin guide, very much worth the trip. There is a marvelous restaurant, nearly tangential to Hammertown, called Gigi's, and both embody the spirit of the region to a tee. From local goods to the foods of the farmers, growers and fishermen of the Hudson Valley. We were the branding/marketing/advertising agency that launched The Hudson River Club the first great restaurant in NYC to champion those very farmers, growers and fishermen, so this is a connection with great personal resonance for me.

There is a Hammertown outpost in the darling town of Millerton and also a Hammertown Barn location in Great Barrington, Mass, very convenient for those of you headed to Lennox and Stockbridge for the summer. And the mother of all Hammertown Barns - the one closest to Kent, and therefore, the Hammertown Barn in which we shop, the original barn in Pine Plains. If I had nothing else pressing (like running a business or finishing the next book), I think I would love to put my shoulder to the wheel in an even more concentrated effort to help to expand that Hammertown idea, as hatched by its founder, Joan Osofsky and her family.

Reflecting the joys and the challenges of her customer's lives, Hammertown is not bound by a price point or even a category of merchandise. It is truly a lifestyle store - from the proverbial soup to nuts. From food to furniture, bedding to baby's gifts, rugs to earrings and all the way to the occasional novel (mine), design book, cook book, or letter opener that Joan just knows will fulfill her customers. There is an innate sense of style and grace that comes from living in a part of the country that is not swayed so much by fashion or status, as by beauty and connection - and by the development of something we champion here at MEIER: a real sense of Authentic Style.

For those of you who have not ventured into a Hammertown Barn, there is the website,

http://www.hammertownbarn.com. And it's great. But I urge you to hop a plane or train or bus, pile into your dad's Oldsmobile, hitch a ride, or buy a Bentley - but get yourself up to a Hammertown Barn. You'll see just what I mean.