The Worth of Women

Wednesday, May 26, 2010

To the best of my knowledge, John Roberts’ wardrobe never raised an eye in any debate, media or otherwise. Neither Scalia’s waistline nor his balding, Brylcreamed hair-do have a caused us to question his allure. And if we don’t choose to consider Clarence Thomas the Cary Grant of the Supreme Court, neither do we think of him as an object of desire. In fairness, we never heard a lot about Ruth Ginsberg’s clothes or Sandra Day O’Conner’s headbands, but they were protected. They were married. Some man had, apparently, found them “desirable,†and therefore, a significant part of their worth was verified and measured. Fascinating and kind of horrifying, but it’s not as though I haven’t seen this before.

Back in the 1970’s, I pulled together a few concept boards about the way women were portrayed in advertising for The National Organization for Women. I pasted up a series of ads selling cigarettes, cars, booze, gum – things not specifically related to gender. The men in these ads were usually portrayed as individual characters. Were they single? We didn’t know. They gave us no hint to their value in the rest of the world – they were there to act as The Purchaser or the End User. Whether they were riding into the sunset with a lit Marlboro, buying a pack of Trident or test-driving a Corvette, they stood in for ‘us’. Except for a suggestion of a ‘hunky he-man’ cowboy (although his smoking friends were as varied in age and girth as Gabby Hayes or Andy Divine), these men were not chosen on the basis of unusual attractiveness. They weren’t ugly, they weren’t dishy; they were meant to be ordinary men. Human men. Everyman.

On the other hand, women in ads were always identified as something other than Everyman. Something in reference to him. A girlfriend, a mother, a wife, and most often, a temptress – flirting with the seller or the audience. Identifying the audience as male, or suggesting that we could be just as alluring if we too used the shampoo, mouthwash or cake-mix. Rarely do we ever see a woman in advertising where the story of her importance within the culture is not spelled out in regard to her position to boyfriends, husbands or family. Is she Single? Is she Married? Is she a Spinster? Somehow, in advertising, we always know. And if it’s important in advertising, it’s because those of us who create those images understand that it’s important to you.

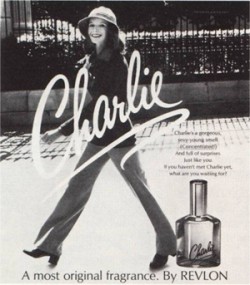

Nearly a lifetime ago I worked on the positioning and launch of Charlie, the Revlon fragrance designed to appeal to “a new breed of young women†emerging in the early 1970’s. The task was clear: we were to appeal to the New Woman; self-actualizing, self-reliant, healthy and happy. We showed no male escort in any of these visuals, we didn’t even show men appreciating the Charlie girl. This long-striding young woman was full of energy, determination, and while she was undeniably attractive, we were careful to create an image of her appeal that was not directed at (or about) men. It wasn’t easy. No flirting with any other character in the shot and no flirting with the camera. No flirting at all! I remember noting as a brief to Bill King, the photographer who shot the very first stills for Charlie. Is she connected to a man? It’s not just that we don’t know – it’s that it isn’t important. It’s not the point of the campaign. She is just a girl – a happy, ambitious, energetic, self-contained human being. And that’s the way we thought women were going to want to be seen from then on.

It seems a sad joke now, exactly forty years later. Here is Dowd’s comment:

“White House officials were so eager to squash any speculation that Elena Kagan was gay that they have ended up in a pre-feminist fugue, going with sad unmarried rather than fun single, spinning that she’s a spinster.â€

Dowd seems a little huffy about the missed opportunity of Kagan and Sotomayor being portrayed as gals about town, looking for a fix-up with “geek-chic Washington bachelors,†instead of as aging, heavy old-maids, resigned to a “cloistered asexual existenceâ€. But given her callous comments on the hair and the weight and the dumpy wardrobes, these seem to be the only two choices Dowd can imagine. And one has to wonder, not just what’s “off limits†in terms of unnecessarily hurtful remarks, but -- far more telling – what Maureen Dowd considers important when adding up a woman’s value.

Speculating that a woman of real quality has been “passed-over†by choice or design in the romance column is, we know, none of our business. But we may not realize that when we do speculate, we add to the weight of thought that keeps women forever bound to a value system intent on the fact that our attractiveness to men is seen, in this culture, as our first and best commodity.

And whether striding up an avenue alone or joining the highest court in the land, women who come up short when measured on the starlet/model/trophy-wife scale, had better understand that their value as a human being will amount to only a fraction of their worth. The worst part of the story, thank you Maureen, is that it isn’t only men who do this to us.