The Role Model

Tuesday, June 15, 2010

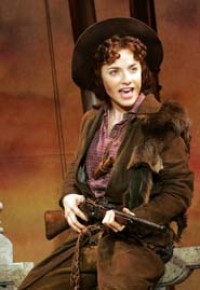

Jenn Gambatese in

Annie Get Your Gun

(© Diane Sobolewski)

Annie Get Your Gun

(© Diane Sobolewski)

Frank drove through the deluge. Never complaining, only supporting me. This is your public, he said. You owe them your attention and I’ll get you there. And so he did. And so he always has.

Weather or not, since we were in the town of the Goodspeed Opera House, we decided to make an evening of it and see the show; as it happened, Annie Get Your Gun, which won’t surprise too many of you to learn was my high-school starring role. Annie is a marvelous role model, for all kinds of reasons. She was a champion of women’s suffrage, taught more than 15,000 women to shoot, because she believed it developed focus, stamina (and certainly acted as defensive protection). Oakley sued a newspaper who launched a paper-selling celebrity lie about her, and won -- without taking a gun from her holster. And she did, indeed, fall in love with her first shooting rival, the marksman, Frank Butler, whom she married when she was just twenty-one years old. They built a career together that included the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show. She performed and won contests right up until her death, in her mid-sixties. Butler, inconsolable, died eighteen days later. Their real love story, far beyond the stage performance, seems all the more wonderful when you learn of the actual ways they crafted and protected their â€brand†and how they donated what was, in those days, a literal fortune of earnings toward women’s rights and charities.

The play was revised for the 1999 Broadway revival to correct the blatant racism in its portrayal of Native Americans and the level of sexism that might have made characters unsympathetic. In the original stage-play, Annie threw a contest because Frank’s pride wouldn’t allow him to lose a shoot-off to a woman. In doing so, she won her man. The new version has them each fake a loss to create a shared end to the shoot-off, winding up in each other’s arms as they recognize the generosity of the gesture. A far kinder, gentler landing, but interestingly, none of it as supportive as the real Frank Butler was to the real Annie Oakley. The true partnership and solid commitment that sustained them for more than forty years – the kind of love you hear people say will only happen in the movies – must have seemed too good to be true to Herbert and Dorothy Fields, the brother and sister writing team of the original 1945 play.

What a missed opportunity. We don’t get much direction in the mythical or instructive ways women can be supported as leaders, while loved as partners. In the world of entertainment, we nearly always have to pay for our gains. Usually on the home front. “The woman who has her career, but an empty life to come home toâ€. We’ve seen all of those movies. All of those plays. I think they’re meant to scare us – and they do!

Wouldn’t it have been just great to actually see how Butler and Oakley managed it – forty years of maintaining a woman’s professional reputation in a job very few women would ever have attempted, and ending up more in love than ever? Wouldn’t you pay to see that show?